Introduction

As I write this, I am reminded of the opportunities and challenges associated with living in Queensland. While many of us enjoy Queensland’s warm sunny climate and the lifestyle opportunities it affords, we are currently working with many communities across the state who have been significantly impacted by major flooding in the northern part of the state and Tropical Cyclone Alfred in south-east Queensland. In addition, the summer’s warm and wet conditions have seen Queensland’s largest recorded outbreak of melioidosis in the Far North with associated tragic fatalities. There have also been locally acquired mosquito-borne Dengue fever cases in and around Townsville, our first human cases of Japanese Encephalitis virus (JEV) since 2022 and positive JEV detections from mosquitos in Darling Downs, Wide Bay and Brisbane.

The theme of this Chief Health Officer’s report is the future of public health. It reinforces our shift in focus from the COVID-19 pandemic to the current and future health challenges that face Queensland, many of which are global and some of which are particular to our state.

Since the last report, there have been notable changes in several headline health indicators reflecting our changing and ageing society. Several gains have been made, such as the over 50% decline in daily smoking since 2002 that has saved the lives of tens of thousands of Queenslanders. This has contributed to decreasing hospitalisation rates for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is most commonly caused by smoking, and shows how addressing modifiable risk factors contributes to the sustainability of our healthcare sector.

However, there has been a rapid increase in the use of e-cigarettes. Between 2018 and 2022, the proportion of adults who currently vaped increased 4-fold. Since then, both Queensland and Australian Governments passed legislation to provide tighter regulation of vaping, and we will monitor these trends.

Being overweight (including obesity) is now the leading modifiable risk factor for total health burden, surpassing tobacco use. The burden arising from poor health continues to increase and now accounts for 54% of the total health burden nationally. In Queensland, hospitalisations due to dementia have already increased by 12.5% from 2015–16 to 2022–23. Cancer incidence in young people is a growing global concern.1,2 This is seen for pancreatic and colorectal cancer in Queensland. And while we are making gains in the prevention, early detection and treatment of cancer, the cancer burden will grow as our population ages.

The increase in chronic disease burden is also a sign of our changing lifestyles and environments, including changes in key risk factors such as obesity and poor diet. Populations that experience higher levels of modifiable risk factors are hospitalised at higher rates than their peers, and a healthier population is more resilient to disease and poor health outcomes.

Healthy pregnancy

Pregnancy is a critical time in the life course that can influence the future health trajectory of both the pregnant women and their baby in-utero, in childhood and as an adult. Many health conditions that have large impacts on our health system can be prevented during pregnancy, and the impacts of this are intergenerational.

We know there are some higher risks of birth complications when the mother is older. This report notes that the proportion of Queensland mothers who were 35 years or older at the time of delivery has increased from 19.2% in 2012 to 23.3% in 2022.

There are also some modifiable risk factors in pregnancy that can affect outcomes for mothers and their children. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is now one of the most common medical conditions impacting pregnancy and is associated with future diabetes in both the mother and child. The proportion of women diagnosed with GDM in Queensland increased from 6.8% in 2012 to 16.5% in 2022. Healthy eating, physical activity, and recommended pregnancy weight gain help to reduce the risk of GDM in many women.

Tobacco smoking in pregnancy is associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes and is a main contributor to stillbirth. In 2022, 11% of all Queensland women smoked tobacco in pregnancy, with a higher proportion reported in First Nations women. We do not yet have data on vaping during pregnancy. However, we are seeing gradual reductions in tobacco smoking over time from 2015.

Queensland Health offers a variety of tailored quit smoking support programs and tools at Quit QH.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is the most common cause of respiratory illness among infants and there is evidence of a link between RSV infection during infancy and asthma during childhood.3–5 In 2024, all pregnant women and babies born in Queensland birthing hospitals became eligible for a free RSV immunisation.6 Early results show that the program has substantially reduced RSV hospitalisations among infants,7 highlighting the broader importance of immunisation for pregnant women, infants and young children.

Healthy environments

Climate

In 2024 and into 2025, one of our biggest assets, the Queensland climate, tested our emergency, disaster, and public health systems. In 2024, Queensland experienced:

- four heatwave events

- 17 heavy rainfall or flooding events including three tropical cyclones

- and a rare “gustnado”, a non-supercell tornado, on the Brisbane River.

Nationally, 2024 was the second-warmest year since records began in 1910, rainfall was 28% above the 1961–1990 average, and annual sea surface temperatures for the Australian region were the warmest on record.8 Our changing climate is anticipated to add extra pressure to our communities, social and healthcare infrastructure, and economy.

Our environment and our health are intertwined—from our climate, our diverse ecosystems and wildlife, our agricultural and livestock practices, to our growing population. Changes in climate patterns will therefore continue to affect our health both directly and indirectly. For example, climate-dependent mosquito-borne diseases may result in some diseases appearing in new locations, disappearing from others, and new diseases emerging. And our growing population will see communities expand into new areas, potentially increasing contact between people and wildlife with corresponding potential for zoonotic disease transmission.

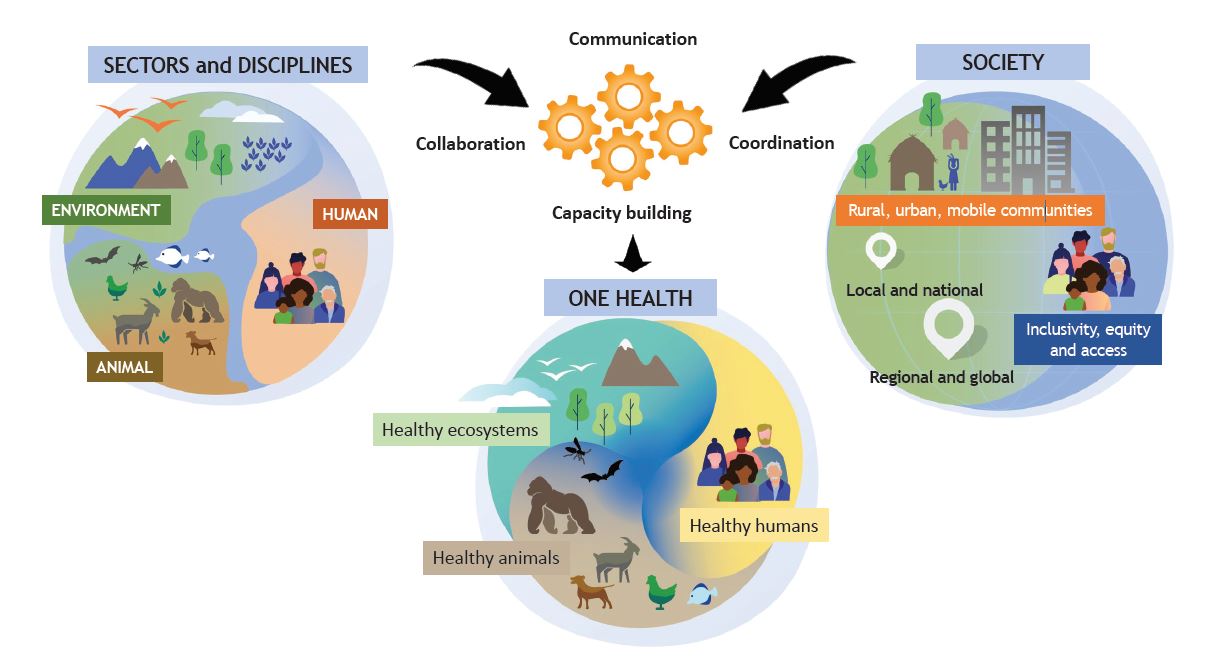

One Health and antimicrobial resistance

Queensland is a national leader in responding to health challenges using One Health principles. This approach involves collaborating across human, animal, plant and environmental sectors.9,10 The previous CHO report included a feature on the success of a One Health response to zoonotic disease outbreaks using a case study of a mosquito-born Japanese encephalitis (JEV) outbreak. That 2022 outbreak was successfully contained largely due to the coordinated responses from Department of Health, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, general practitioners, primary industry, non-Government organisations, local councils, local landowners, and the general public.

Figure 1: World Health Organization infographic defining One Health principles

One Health is also a priority for the new Australian Centre for Disease Control (ACDC). Our experience in Queensland will be integral in shaping the design of a national One Health response led by the new ACDC.9

One Health principles and new ways of working have benefits for other significant health challenges such as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Globally in 2019, AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million of the estimated 4.95 million deaths associated with drug-resistant bacterial infections.11 AMR resistance from animals can be transmitted to humans through various pathways such as:

- food consumption

- direct contact with animals

- environmental exposure including from humans to animals.

Fortunately, Australia’s use of antibiotics in food producing animals is one of the lowest in the world, and there are well-defined safeguards.12 However, Queensland’s unique environment, enjoyed by 2.1 million international and 25.6 million domestic visitors in the year ending June 2024,13 brings with it an increased risk of local transmission resulting from overseas-acquired AMR exposure.

A focus on the increased risk of AMR is important. A study estimated that in 2020 there were 1,031 AMR-associated deaths with associated hospital costs of $72.0 million, costs associated with premature death of $439.0 million, and the loss of 27,705 quality-adjusted life years in Australia.14 A new World Health Organization (WHO) study indicates that improving vaccine use against 23 pathogens could reduce global antibiotic consumption by 22% annually. Globally, the annual treatment costs for AMR are estimated at $730 billion with widespread vaccine rollout potentially saving a third of those costs.15

Hosting the 2032 Olympics

Just as Queensland has considerable experience in planning for natural disasters and disease outbreaks, advance planning is essential for the hosting of an Olympic games. Queensland Health is focused on managing health risks associated with this event. Various steps are underway to ensure that Brisbane not only excels at hosting the 2032 Olympics, but that it is a global leader in providing a safe Games experience.

In addition to the risks of importation of anti-microbial resistance that were described in the One Health section above, there are also communicable disease risks. People may recall the steps taken to manage Zika Virus during the Rio de Janeiro games in 2016, and the initial deferral of the Tokyo games in 2020 due to COVID-19, and then the subsequent management of COVID-19 amongst athletes and spectators in Tokyo in 2021.

Our health system planning for the 2032 Olympics includes enhanced surveillance and detection systems, and we will be capitalising on the opportunities offered by better data integration and live surveillance. Queensland Health is also supporting many of the associated infrastructure changes that accompany an Olympic Games so that they can offer health benefits. For example, the Healthy Places, Healthy People initiative helps planners mitigate health impacts associated with the heat and sun in open spaces, including using a system that optimises tree shade and reduces UV exposure with different tree forms, sizings, and spacing intervals.

Healthy Places, Healthy People highlights the opportunities associated with "healthcare in the information age".

Healthcare in the information age

The healthcare sector is undergoing a transformation that promises to revolutionise patient care, improve health outcomes, and increase efficiency. However, this transformation also brings new risks and challenges that must be carefully navigated.

As artificial intelligence (AI) and digital technologies continue to shape healthcare, we have a responsibility to ensure they are safe, reliable, and continue to meet ethical standards.16-18 Among emerging technologies, AI stands out as a powerful tool with wide-ranging potential applications in healthcare. However, AI systems can inherit human biases and amplify algorithmic disparities, impacting health outcomes and public trust.19

In contrast, there are many beneficial applications. AI can enhance productivity, improve patient safety, detect diseases, and enable more accurate diagnoses and personalised treatment plans. For example:

- By rapidly analysing a broad range of data sources, AI can be used in syndromic surveillance to enhance earlier detection of disease outbreaks and help prepare health systems. In one example, an Australian AI system deployed in Africa monitored social media posts for keywords like “fever” and “rash”. It alerted health systems to a potential Ebola outbreak that was declared by the WHO three months later.20

- AI-driven tools help reduce clinicians’ administrative burdens, assist with medication management, answer health queries, and track symptoms.16,21

As the information age influences many aspects of the healthcare sector, we will be both cautious and optimistic about this evolution.

Digital Health 2031 outlines the digital vision for Queensland’s health system and the national strategy is Discover the National Digital Health Strategy (2023–2028).

Future Challenges

The 2025 CHO Report highlights important demographic trends that our health system will monitor. For example:

- While mortality from many cancers is declining, we have seen that the rates of some cancers—notably colorectal and pancreatic cancers—are increasing in young people.

- Regional or disadvantaged areas have poorer health outcomes across many measures (Figure 2), and this is particularly the case for First Nations peoples. While there have been gains in life expectancy and improvements in some health measures, there are also health conditions that disproportionately impact these communities.

- We expect to see dementia become the leading cause of death for all Queenslanders in the near future, noting it is already the leading cause of death among Queensland women.22

Figure 2: Queensland disparities in health outcomes and modifiable risk factors

On this last point, we’ve known for decades that the population is ageing as mortality and fertility rates decline. Over the next 40 years, Commonwealth health spending is projected to increase from 4.2% to 6.2% of GDP. The main driver is the ageing of the population—nationally, the population of adults 65 years and older is expected to more than double and to more than triple for those 85 years and older by 2063.23

By analysing how population changes affect hospitalisations, we can estimate how many episodes of care may be needed as the population ages. The results are sobering. There is projected to be a 45% increase in the population 70 years and older, increasing from about 630,000 in 2022 to 911,000 in 2032.

Based on current trends, hospitalisations for those 70 years and over would increase over 44%, from 958,000 in 2023–24 to 1,378,000 in 2032–33.

This high demand for health services is anticipated to last for a considerable period as those 70 years and older continue to age. To see the effects of population changes refer to Ageing and future healthcare demand.

Many of these additional hospitalisations stem from lifestyle risk factors that are modifiable. For example, dementia hospitalisations are increasing, and its modifiable risk factors include alcohol consumption, obesity, depression, diabetes, hypertension, physical inactivity, sensory loss, sleep disturbance, smoking, and social isolation.24-26

We know about the links between good health and positive lifestyle factors like regular exercise, healthy eating, social engagement, and other healthy choices. Queenslanders certainly live in the right place to capitalise on these positive lifestyle factors and enjoy long healthy lives.

Figures on this page are interactive

To learn more about how to navigate interactive figures, dashboards, and visualisations see About this Report.

References

- Ugai T, Sasamoto N, Lee H-Y, et al. 2022. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications, Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 19(10):656–673, doi:10.1038/s41571-022-00672-8.

- Zhao J, Xu L, Sun J, et al. 2023. Global trends in incidence, death, burden and risk factors of early-onset cancer from 1990 to 2019, BMJ Oncology, 2(1):e000049, doi:10.1136/bmjonc-2023-000049.

- Coutts J, Fullarton J, Morris C, et al. 2020. Association between respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in infancy and childhood asthma, Pediatric Pulmonology, 55(5):1104–1110, doi:10.1002/ppul.24676.

- Shi T, Ooi Y, Zaw EM, et al. 2020. Association Between Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Acute Lower Respiratory Infection in Early Life and Recurrent Wheeze and Asthma in Later Childhood, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 222(Supplement_7):S628–S633, doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz311.

- Rosas-Salazar C, Chirkova T, Gebretsadik T, et al. 2023. Respiratory syncytial virus infection during infancy and asthma during childhood in the USA (INSPIRE): a population-based, prospective birth cohort study, The Lancet, 401(10389):1669–1680, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00811-5.

- Queensland Government. 2024. RSV immunisations, https://www.vaccinate.initiatives.qld.gov.au/what-to-vaccinate-against/rsv-immunisation, accessed 14 November 2024.

- Australian Medical Association Queensland. 2024. RSV rate among babies drops dramatically, https://www.ama.com.au/qld/news/RSV_cases_drop#:~:text=The%20program%20has%20been%20particularly,week%20ending%209%20September%202024., accessed 15 November 2024.

- Bureau of Meteorology. 2025. Annual climate statement 2024, Analysis of Australia’s oceans, atmosphere, temperature, rainfall, water, and significant weather during 2024, http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/annual/aus/?ref=marketing#tabs=Key-points, accessed 15 February 2025.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. 2025. One Health, About One Health, https://www.cdc.gov.au/topics/one-health, accessed 3 February 2025.

- World Health Organization. 2022. One health, Geneva, https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1, accessed 24 March 2025.

- Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, et al. 2022. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis, The Lancet, 399(10325):629–655, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

- Australian Government. 2023. AMR and animal health in Australia, https://www.amr.gov.au/about-amr/amr-australia/animal-health, accessed 11 February 2025.

- Tourism and Events Queensland. n.d. Visitors boosting Queensland’s economy by $95 million every day, News and media, https://teq.queensland.com/au/en/news-and-media/queensland-news/2024/visitors-boosting-queensland-s-economy-by--95-million-every-day, accessed 12 March 2025.

- Wozniak TM, Dyda A, Merlo G, et al. 2022. Disease burden, associated mortality and economic impact of antimicrobial resistant infections in Australia, The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific, 27:100521, doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100521.

- Hasso-Agopsowicz M, Hwang A, Hollm-Delgado M-G, et al. 2024. Identifying WHO global priority endemic pathogens for vaccine research and development (R&D) using multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA): an objective of the Immunization Agenda 2030, eBioMedicine, 110:105424, doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105424.

- CSIRO. 2023. AI trends for healthcare, CSIRO Australian e-Health Research Centre, Brisbane, Queensland, https://aehrc.csiro.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/AI-Trends-for-Healthcare.pdf, accessed 16 February 2025.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. 2024. Safe and Responsible Artificial Intelligence in Health Care – Legislation and Regulation Review, https://consultations.health.gov.au/medicare-benefits-and-digital-health-division/safe-and-responsible-artificial-intelligence-in-he/, accessed 31 January 2025.

- Digital Transformation Agency. 2024. Our next steps for safe, responsible AI in government, https://www.dta.gov.au/news/our-next-steps-safe-responsible-ai-government, accessed 5 March 2025.

- Department of Industry, Science and Resources. 2024. Introducing mandatory guardrails for AI in high-risk settings: proposals paper, https://consult.industry.gov.au/ai-mandatory-guardrails, accessed 24 March 2025.

- CSIRO. 2020. AI-powered tool predicts serious disease three months before official announcement, All news and articles, https://www.csiro.au/en/news/all/articles/2020/april/ai-powered-tool-predicts-serious-disease-three-months-before-official-announcement, accessed 9 March 2025.

- CSIRO. 2025. The Australian e-Health Research Centre: Annual report 2023-24, Canberra ACT, https://aehrc.csiro.au/about/annual-report/, accessed 4 February 2025.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2024. Causes of death, Australia, 2023, ABS, Canberra, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/2023, accessed 10 October 2024.

- Australian Government. 2023. Intergenerational report 2023: Australia’s future to 2063, The Treasury, Parkes, ACT.

- Jones A, Ali MU, Kenny M, et al. 2024. Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors for Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Umbrella Review and Meta-Analysis, Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 53(2):91–106, doi:10.1159/000536643.

- Peters R, Booth A, Rockwood K, et al. 2019. Combining modifiable risk factors and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, BMJ Open, 9(1):e022846, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022846.

- Zhang Y-R, Xu W, Zhang W, et al. 2022. Modifiable risk factors for incident dementia and cognitive impairment: An umbrella review of evidence, Journal of Affective Disorders, 314:160–167, doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.008.